We live in a world of symbols. My wedding ring, for example, reveals much more about me than a simple band of gold. When my wife placed it on my finger, it was transformed into something of far greater significance. Today, it represents 40 years of marriage.

Likewise, the golden arches of McDonald’s in Jerusalem say more than ‘buy a burger here’. They speak to the spread of American culture around the world. Burning a square of white cloth in the street would be deemed odd by passers-by. But if that fabric were covered in the Stars and Stripes of the US flag, then you might spark a riot.

Art is full of symbolism if you know how to look for it. In 1939, the iconologist Erwin Panofsky laid out a three-part process for helping art lovers do exactly that. His theory was based on the example of a man passing a friend in a park. The friend raises his hat in welcome. What does that mean?

On a primary level, the friend is lifting his hat off his head, as though he is making it sit more comfortably. At the secondary level, both friends understand that the hat lift is a cultural gesture of welcome. But then there is the tertiary level. In mediaeval times, friendly knights would remove their helmets and leave themselves open to attack as a show of trust. So, the symbolism has far deeper roots.

Worth a second look

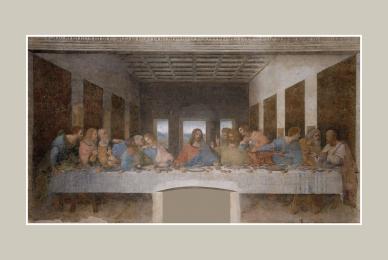

Let's apply Panofsky’s Hat sequence to a pair of famous paintings by Leonardo da Vinci.

This one needs little introduction. At a primary level, we have a group of 13 men at a long dinner table engaged in a heated discussion. The man in the middle is the centre of attention.

At the secondary level, we can use our knowledge of the Bible to interpret this painting as the Last Supper of Jesus surrounded by his 12 disciples on the evening before his crucifixion. The disciples are animated because Jesus has just revealed that one of them will betray him.

When we go to the tertiary level, we will find hidden symbols within the painting that give greater depth to the story. For a start, Leonardo appears to use the number three to structure his masterpiece. The disciples are seated in groups of three, there are three windows, while Jesus himself presents a triangular shape with his outstretched arms. Surely too much of a coincidence.

The painting is a mural in a convent, so most likely the artist wanted to symbolise the Holy Trinity for his devout audience and patron. (Or is it because Peter will deny knowing Jesus three times?)

Leonardo also uses symbolism to identify Judas, the disciple who will betray him. He is shown gripping a small leather bag, presumably filled with the 30 pieces of silver. Look closely, and Judas has also knocked over a pot of salt, which was another symbol of betrayal that would have been well understood by contemporary viewers. He is using his left hand (a sign of bad luck) to pinch a bread roll from Jesus’ grasp, while he is the only disciple to drink milk instead of wine – a premonition that he will not receive forgiveness from the Blood of Christ.

Of course, we can over-interpret symbols in art. In the hugely popular Da Vinci Code novel by Dan Brown, the lady-like figure of John at the right hand of Jesus is presented as evidence that Mary Magdalene joined the supper and was, in fact, Jesus’ wife and the mother of his children.

A nice plot device, although it does beg the obvious question: where was John? Besides, it was quite common at the time to paint younger, unmarried men in a feminine way. Case closed.

A rose by any other name

Here’s another Leonardo: the Madonna of the Carnation.

At face value, it’s a mother showing a carnation to her baby. With a little theological and cultural knowledge, we can make an educated guess that a Renaissance painting of a mother and baby is most likely Mary and Jesus. So, it’s a Madonna.

But what of the carnation? The flower is red like the colour of blood. It therefore represents the Passion of Christ. The infant is reaching up towards it. So, he is accepting his destiny. Even from his first actions as a child, Jesus is saying: I know that one day I'm going to die.

Next time you go into a gallery, try using Panofsky’s Hat as an art detective to uncover the secret clues in the canvas. Or why not drop a few suggestive symbols into your own paintings? Perhaps somebody will be trying to decipher them in five hundred years’ time…

Inspired?

For more food for thought, why not become a member for £15 a year and enjoy our weekly online lectures. Follow the button below for more details.